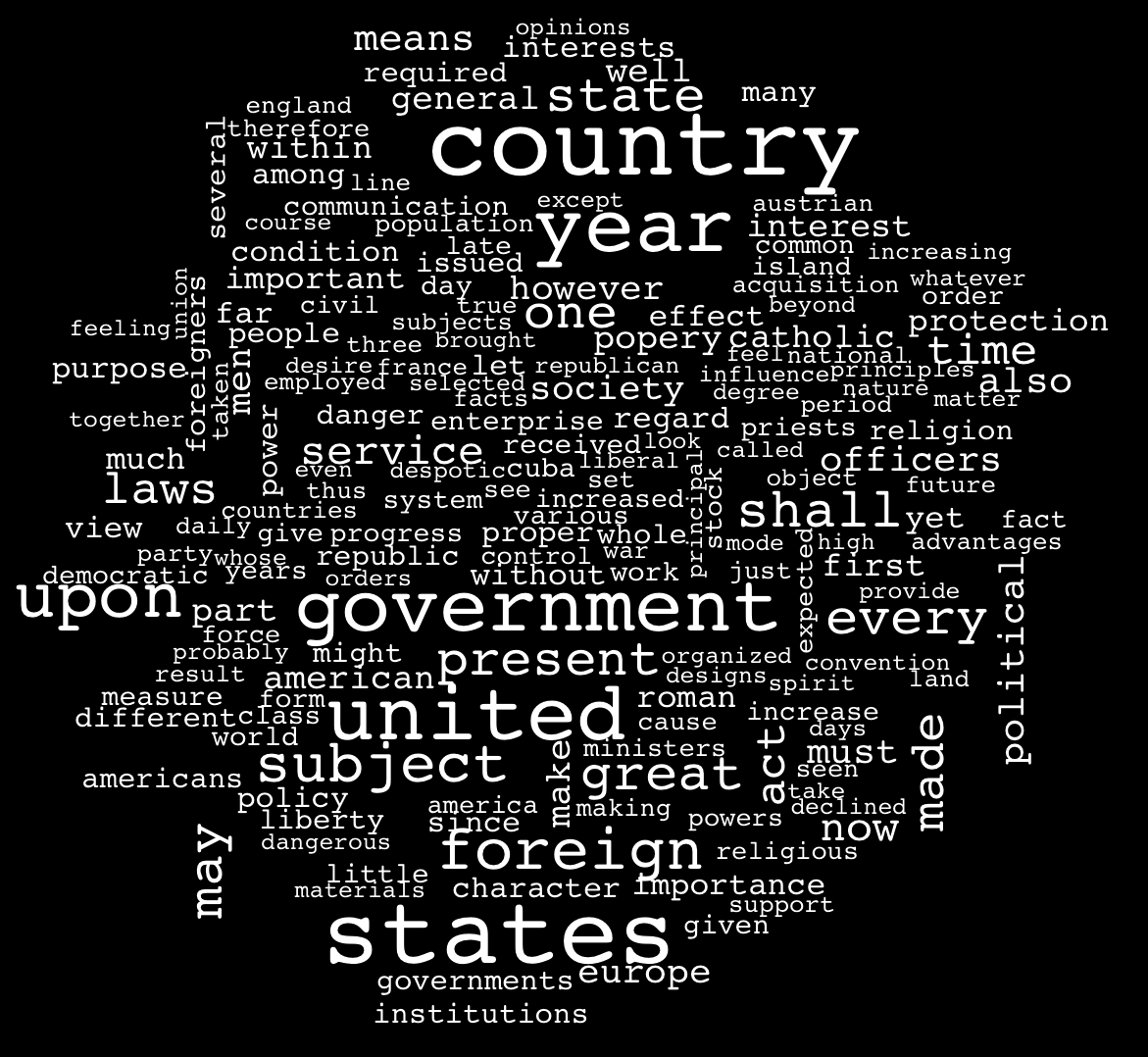

All Nativism

Know-Nothing Party

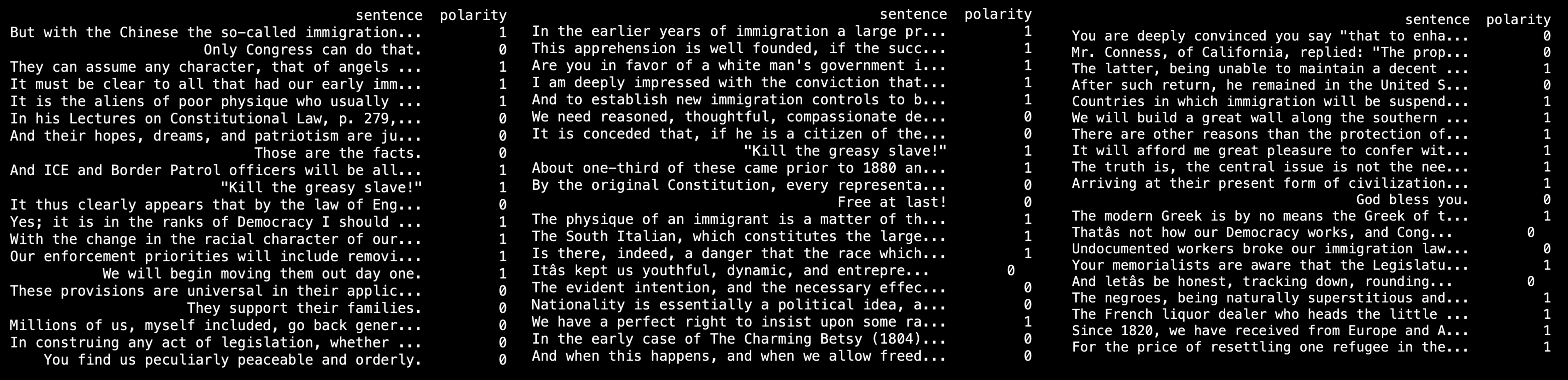

We constructed an extensive sentence database of immgration rhetoric, each hand-labeled either nativist or not-nativist. The database focuses on three nativist movements in the United States during the nineteenth century: the Know-Nothing Party of the 1840s and 1850s, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the latter half of the century, and the debate over Chinese exclusion in the final few decades of the 1800s. In total, the collection comprises six political speeches, three accounts of legislative proceedings, one court case, excerpts from three books, one Ku Klux Klan manifesto, and three compilations of text from newspapers, including editorials and open letters. We also included three more modern speeches, one each from Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Martin Luther King, Jr., to prime our machine learning model on modern diction and speech patterns (see "Machine Learning" for further explanation). In all, we labeled 816 sentences as "nativist" or "non-nativist" during the process of training the model, taking care to attain a roughly equal split between the two categories.

The compilation of this database involved locating source material, converting it into readable txt files, and cleaning the data to remove irrelevant sections of speeches and writings. After some trial and error (and discussion with Boaz Barak of the CS department), we determined that the best strategy was to draw positive (nativist) examples and negative (not-nativist) examples from different sources entirely. We wrote some code to automate the labeling process: we fed it a speech (.txt file), and it displayed sentences one by one which we could designate nativist (1) or not nativist (0) by hand. For nativist speeches, we only included the sentences labeled 1 in the database. In the absence of physical library sources, texts for certain political figures and nativist groups were often unavailable (as discussed in the following paragraph).

Texts on the debate surrounding the Chinese Exclusion Act dominate the database, a skew that resulted from the variance in accessibility of sources across our three focus areas and from the fact that it was easier to find immigration-specific texts for Chinese exclusion. Future, post-pandemic iterations of this project would hopefully have greater access to source materials in order to obtain a more even spread of texts. Nevertheless, the imbalance did not appear to negatively impact our results. As outlined in detail under the "Machine Learning" tab, the model was still largely successful in recognizing nativist rhetoric in the modern presidents whom we analyzed, perhaps because word choice and subject matter of the modern-day immigration discourse aligns more closely with the Chinese exclusion debate of the late nineteenth century. (We still debate how many and what kind of immigrants the U.S. should allow immigrants into the country as happened during the era of Chinese exclusion, but mainstream society generally does not promote ideas of racial superiority, as many of our KKK and Know-Nothing sources do.)

This set of texts includes speeches from Millard Fillmore and Samuel F.B. Morse. Millard Fillmore was the thirteenth president of the United States and member of the Know-Nothing Party. (One of Fillmore’s speeches provides the text that we used to create the image on the homepage of this website.) Two of his State of the Union addresses responded to calls for U.S. territorial expansion into the Caribbean. Regarding Cuba, Fillmore employed nativist language:

"Were this island comparatively destitute of inhabitants or occupied by a kindred race, I should regard it . . . as a most desirable acquisition. But under existing circumstances I should look upon its incorporation into our Union as a very hazardous measure. It would bring into the Confederacy a population of a different national stock, speaking a different language, and not likely to harmonize with the other members."

Samuel F.B. Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, was also a prolific writer on immigration and member of the Know-Nothing Party. While Fillmore’s nativism tended to be presented in racial terms, Morse was staunchly anti-Catholic. In his 1835 book Imminent Dangers to the Free Institutions of the United States: Through Foreign Immigration and the Present State of the Naturalization Laws, he warned that allowing Catholics to "overspread this country" would "surely overthrow our institutions and gradually bring us under a form of government" contrary to democratic principles.

Of the three movements under analysis, availability of online-accessible primary source texts was the most limited for the KKK. We began with the 1868 "Constitution of the Ku Klux Klan," which outlines the beliefs and structure of the organization. We also extracted excerpts from The Ku Klux Klan, a pro-KKK book written in the early twentieth century by Amy Cooper Burton. In her defense of the organization, Burton advocates for the need "to scare into submission the unruly free negroes and the trouble-making carpetbaggers." Elsewhere, she sets up a racial hierarchy, casting Black Americans as childlike (calling them "naturally superstitious and imaginative," for instance) and inferior to white Americans.

As previously mentioned, sources related to Chinese exclusion make up the bulk of the database due to availability online. The sources are quite diverse. The earliest Chinese exclusion text in the database comes from People v. Hall, an 1852 California Supreme Court case that denied Americans of Chinese descent the right to testify against white citizens. Around the same time, California governor John Bigler delivered a speech before the state legislature that advocated for limitations on the rights of California residents of Chinese descent. The inaugural address of Governor Leland Stanford echoed this same sentiment ten years later and more explicitly outlined his beliefs in the superiority of the white race. In the 1880s, members of Congress argued in favor of an act prohibiting Chinese immigration—we gathered excerpts of speeches from Representative William Higby of California, Senator Henry W. Corbett of Oregon, and Representative Horace Davis of California. Similarly, an 1877 record of deliberations in the California state legislature contained discourse on Chinese immigration with nativist threads. We rounded out our survey of the Chinese exclusion debate with selections from an 1894 publication by the Immigration Restriction League, a document that included full-length anti-immigration opinion editorials as well as excerpts from nativist rhetoric printed in prominent newspapers at the time.

To train the model to recognize language that casts immigration in a positive light (and thereby prevent it from labeling any sentence related to immigration as nativist), we also used an 1852 published letter from a Chinese immigrant to immigration hardliner Gov. Leland Stanford of California as well as chapter from The Chinese in America, a book written in defense of Chinese immigrants by Otis Gibson, a Methodist missionary in California.

We also used three modern speeches to familiarize the model with present-day diction and syntax—Barack Obama’s "Address to the Nation on Immigration" on November 20, 2014; Donald Trump’s address on immigration at a campaign rally Phoenix, Arizona, on September 1, 2016; and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s "I have a Dream" speech from the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. (The MLK speech does not deal exclusively with immigration; its purpose was to provide data on the form of both modern and positive rhetoric.)

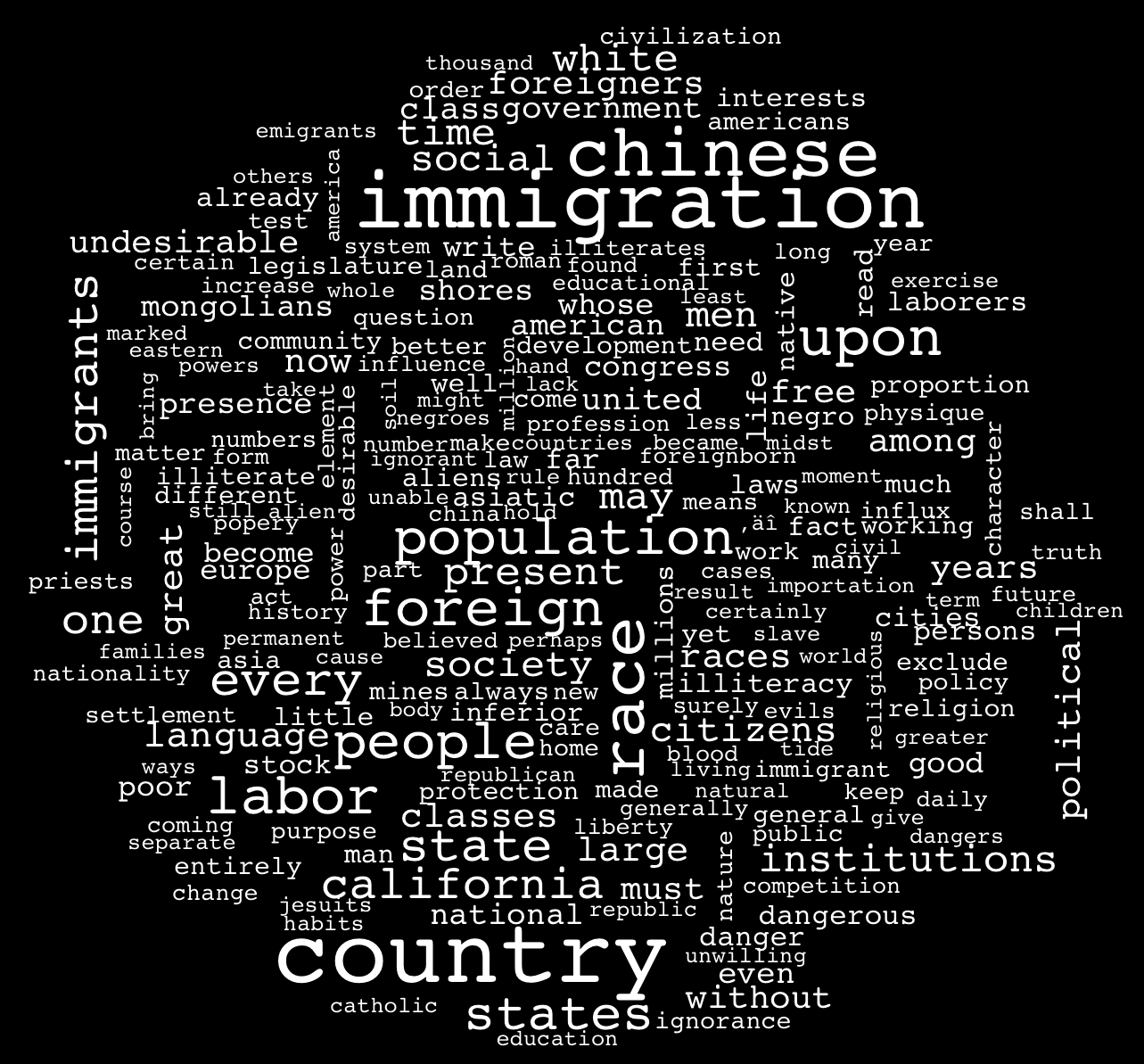

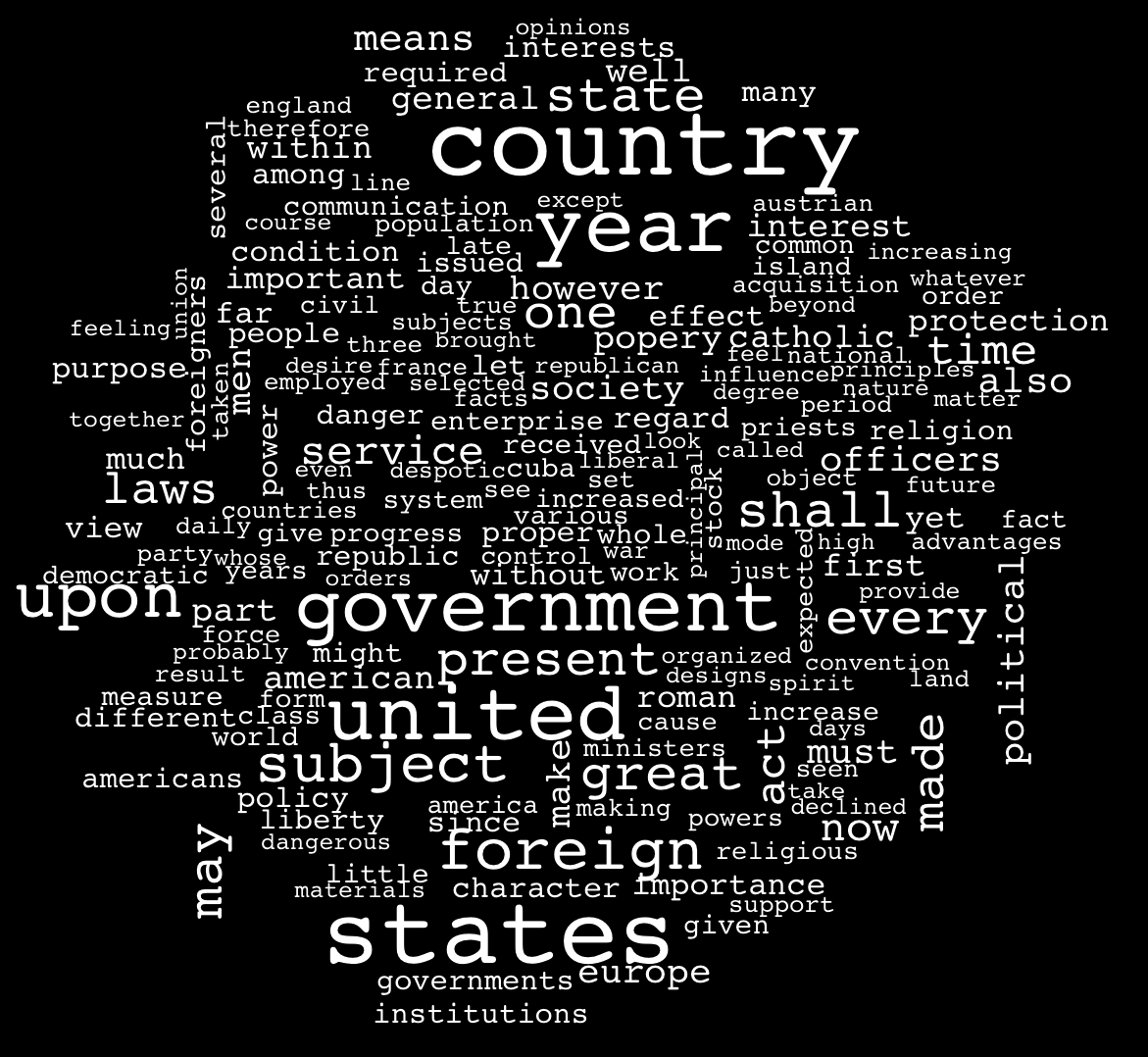

Though not as robust as the findings from the machine learning analysis, these word clouds still paint broad strokes of trends in each of our three categories.

The "All Nativism" cloud—an amalgamation of nativist-labeled sentences from all three focus areas included in the database—demonstrates a few key concerns permeating nineteenth-century discussions of immigration. For instance, the high frequency of "race" and "population" reflects a racist concern among nativist orators that an influx of immigrants will corrupt the "racial purity" of the country’s population—Samuel F.B. Morse and Leland Stanford lay out this fear explicitly in their speeches and writings. Similarly, nativist speeches often warned that immigrants would destroy American "institutions" or irreparably corrupt the "labor" force.

The other three word clouds are composed of all sentences from each focus area, not just sentences marked as nativist. Like the overall word cloud, they offer general insights about each nativist movement. The Know-Nothing cloud, for example, contains themes absent in the other focus areas like "Catholic" and "despotic," and we see a concern over the alleged destruction of the United States government and democratic institutions at the hands of immigrants.

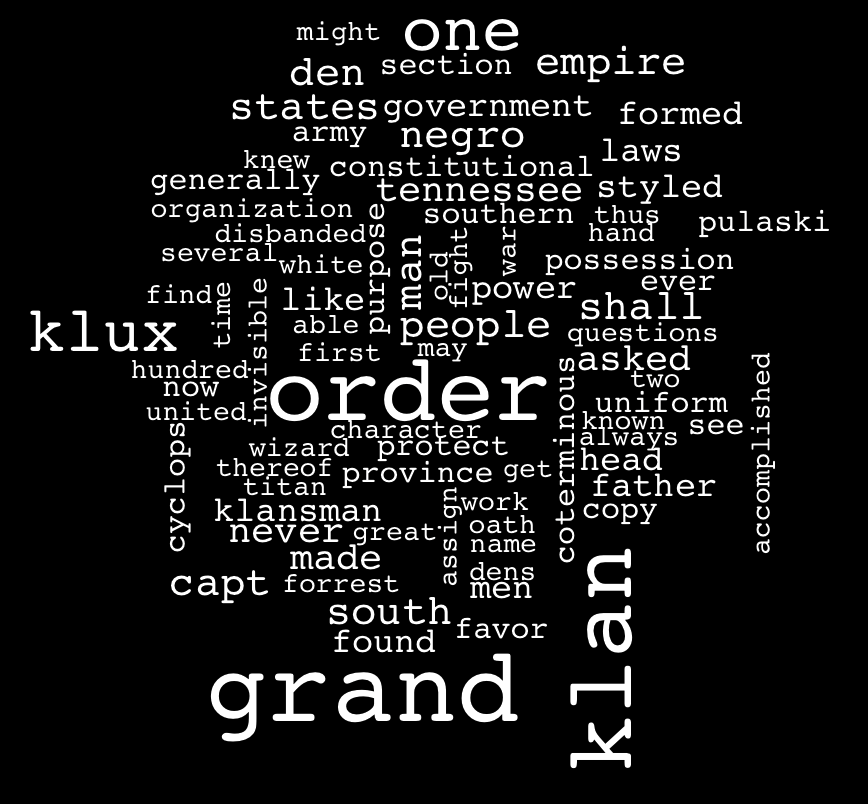

Additionally, though words like "order," "Grand," and "Klan" indicate that much of the KKK text was centered on the structure of the organization, the Ku Klux Klan word cloud also indicates the Klan members thought of themselves as belonging to a cohesive national movement with words like "empire," "government," and "constitutional."

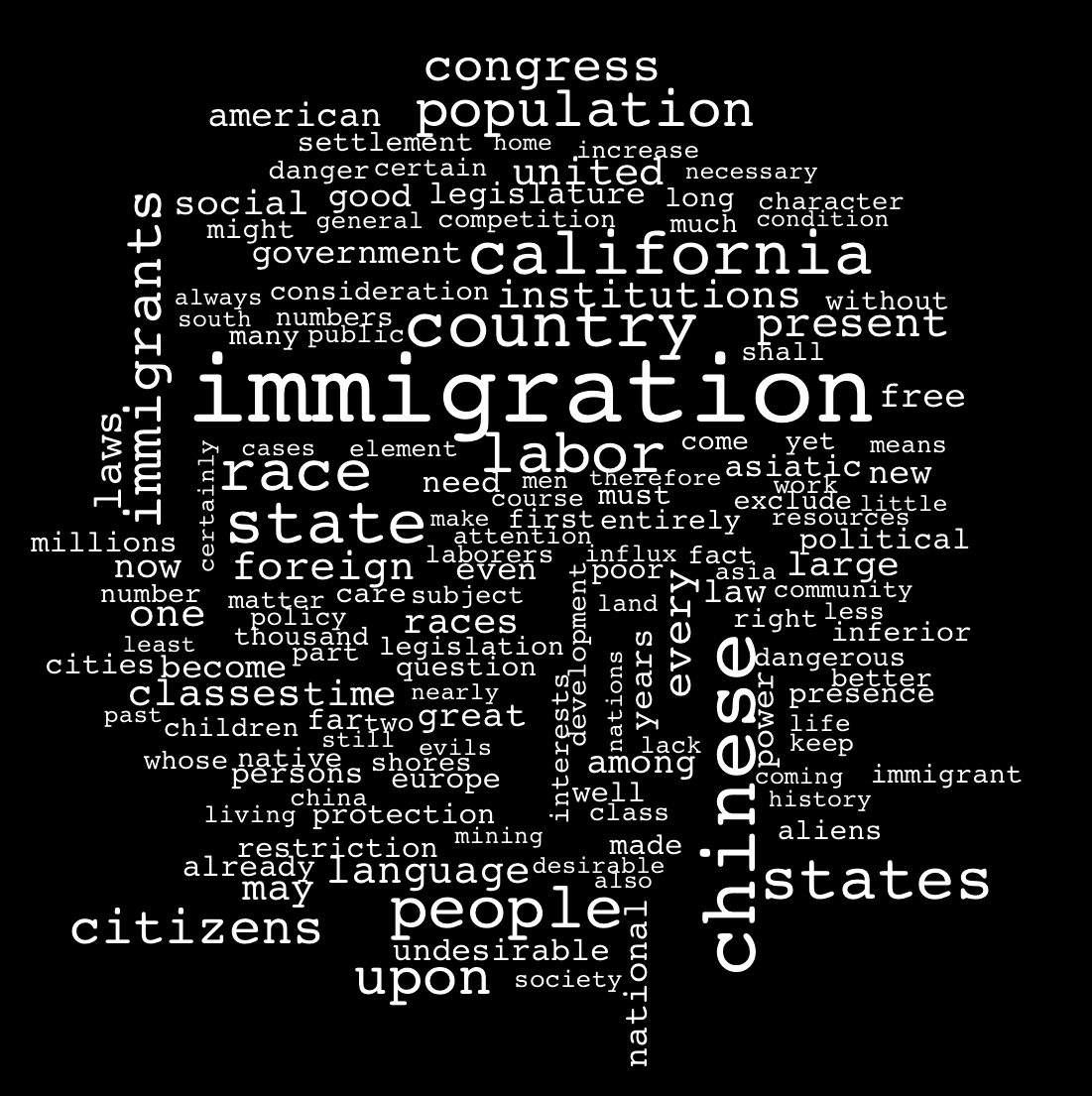

Finally, notable words from the Chinese exclusion cloud include "citizens" and "language"—beginning with People v. Hall, the question of the rights of citizenship was at the forefront of the Chinese immigration debate, and linguistic and cultural differences often provided the basis for discrimination against Chinese Americans, especially on the West Coast.