Nativism is defined as "a deep-seated American antipathy towards internal 'foreign' groups of various kinds—cultural, national, religious, racial—which has erupted periodically into intensive efforts to safeguard America from such perceived 'threats'" [1]. Though nativist rhetoric has grown more visible in recent years, the history of nativism in the United States did not begin with Donald Trump or David Duke. In fact, the history of American nativism begins before the founding of the nation.

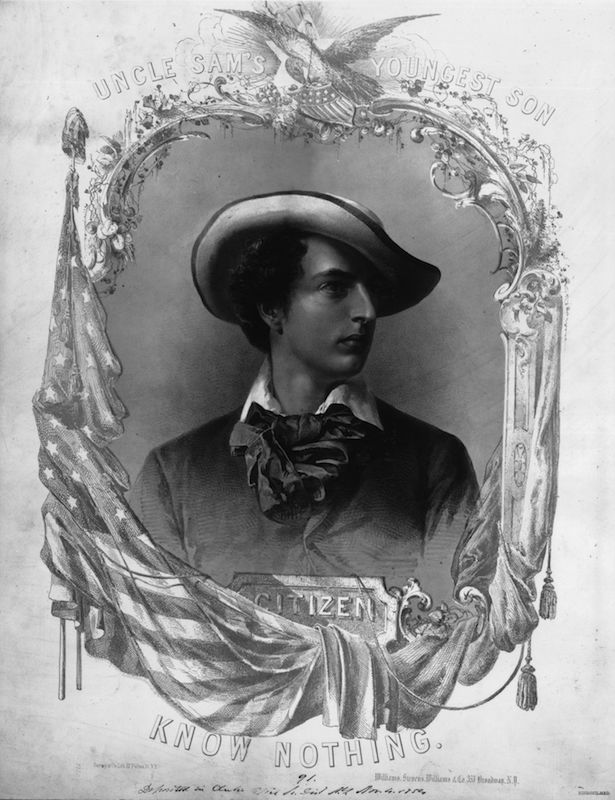

One of the earliest roots of nativism in colonial America was anti-Catholic sentiment. Before independence, the colonies hosted considerable religious diversity, though there was a "generalized Protestant identity" [2]. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, a strain of anti-Catholicism dominated British culture as a result of ongoing war with France and circulation of popular pamphlets. This sentiment extended to the colonies—before 1700, only Rhode Island gave Catholics full religious and civil liberties [3]. The trend continued after independence. In early nineteenth-century history texts averred that "the true religion is patently limited to Protestantism," depicting Catholicism "not only as a false religion, but as a positive danger to the state; it subverts good government, sound morals, and education" [4]. These restrictions on Catholics in the law and education coincided with the cropping up of numerous anti-Catholic fraternal societies among the civic assocations of the 1820s and 1830s [3]. By the 1850s, this anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic fervor took political form—in 1849, Charles B. Allen of New York established a secret society that would come to be called the Know-Nothings [6]. They professed opposition to any foreign-born or Catholic political candidate and advocated for lengthening the period of naturalization to twenty-one years [7]. Prominent members included author and inventor Samuel F.B. Morse as well as United States President Millard Fillmore.

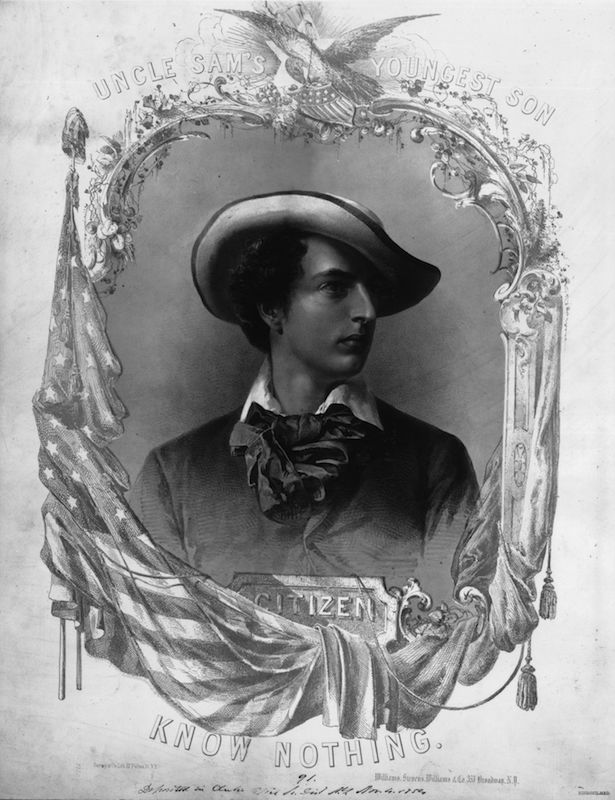

The Ku Klux Klan, perhaps the most infamous nativist organization in the United States, took a far more racialized approach to their hatred of the "foreign" than the Know-Nothings, though their branch of nativism also has roots in the colonial era. At and following American independence, a pervading myth held that the supposedly egalitarian society established in the United States was descended from a noble race of Anglo-Saxons who originated in Britain; some even claimed that these Anglo-Saxons "carried a desire for freedom in their veins, and had a destiny to realize this impulse" [8]. During his stay in the United States, Alexis de Tocqueville quipped that "There is hardly an American to be met with who does not claim some remote kindred with the first founders of the colonies; and as for the scions of the noble families of England, America seemed to me to be covered with them" [9]. This idea of a pure, noble Anglo-Saxon heritage that connected white Americans to the Founding Fathers applied handily to racial hierarchies created by slaveholders in the South. Following the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the Ku Klux Klan emerged in Tennessee in 1866 as a fraternal society of former Conferedate soldiers [10]. In 1886, the document "Organization and Principles of the Ku Klux Klan, 1868" (a text featured in our database) outlined the Klan's opposition to "Negro equality both social and political" and support for the "reenfranchisement and emancipation of the white men of the South" [11]. Throughout the Reconstruction era, the Klan violently sought to manifest this belief in an immutable racial hierarchy, terrorizing Black men, women, and children and hindering efforts to grant civil liberties to emancipated slaves [12].

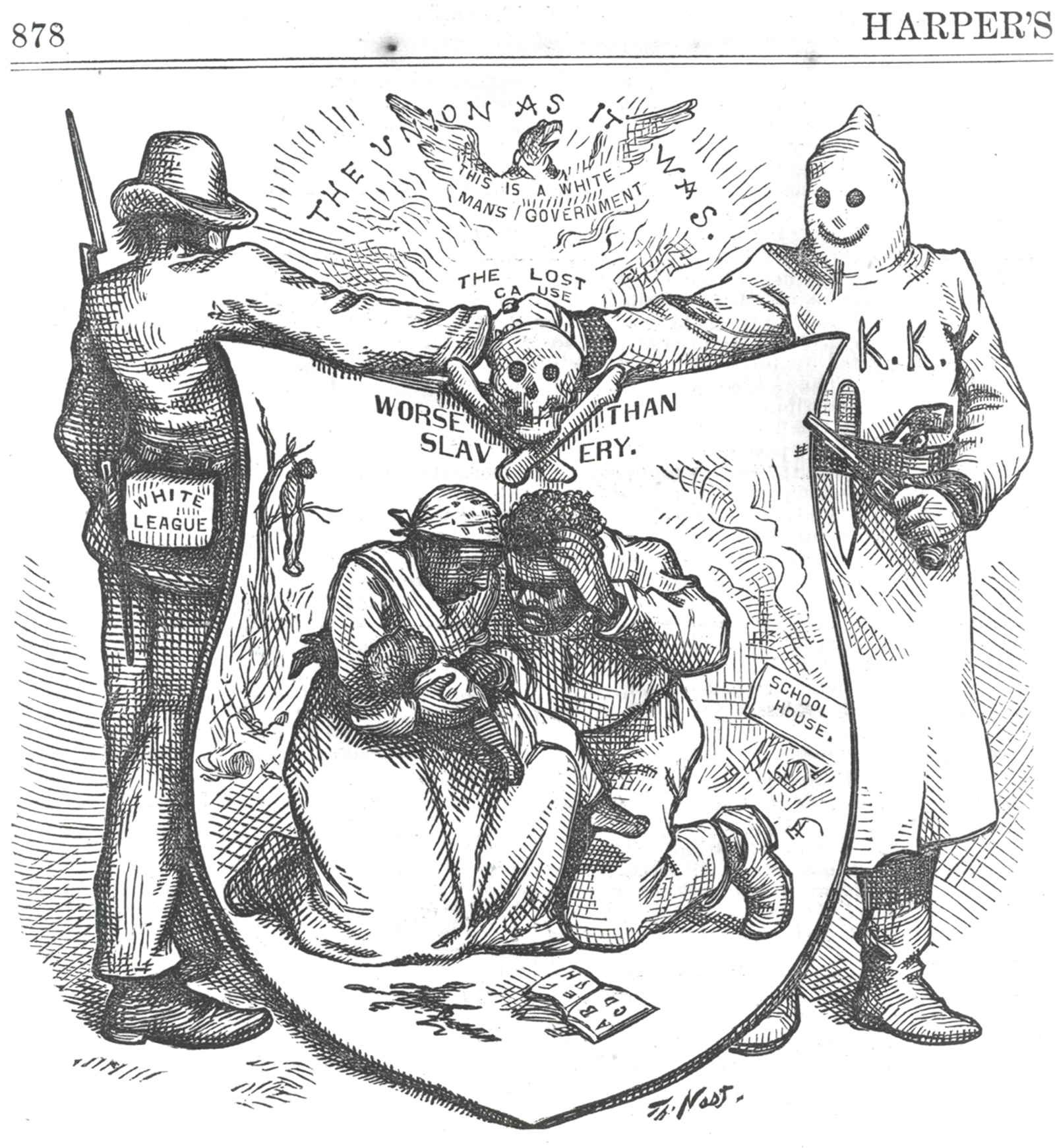

The postbellum period also ushered in another nativist moment, the movement against Chinese immigration on the West Coast. Animosity toward Chinese immigrants had been building since mid-century, partially because of agitation by California's working class, who resented competition in the job market [13]. This racial animus resulted in a marked stripping of rights from Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans. The 1857 state constitution of Oregon, for example, "barred 'Chinamen' from owning real estate" [14]. Additionally, the California Supreme Court decision in People v. Hall (the text of which is included in our database) prevented Chinese immigrants from testifying against white Americans in court and cast these immigrants as entirely inferior to whites, calling them "incapable of progress or intellectual development beyond a certain point, as their history has shown" [15]. Politicians debated solutions to this "problem," often employing nativist rhetoric in doing so. Interestingly, these nativists distinguished between European (usually Northern) immigration in the time of the Founders (which they professly admired) and all other immigration. California governor John Bigler, for instance, commended the U.S. for historically opening "its paternal arms to the "oppressed of all nations," and [offering] them an asylum and a shelter from the iron rigor of despotism" [16]. But this openness to immigration did not extend to the newer waves of Chinese immigrants. Representative Horace Davis of California reflected resistance to Chinese immigration, asserting that "the presence of so large a foreign body unable or unwilling to assimilate to our ways renders them a dangerous element to society and a grave peril to the State" [17]. Ultimately, nativists won the debate, and Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882, barring all Chinese immigration and eliminating any path to citizenship for Chinese immigrants already in the U.S. [18].

From the turn of the twentieth century to today, nativist currents have ebbed and flowed, taking on a variety of forms. Early in the century, disdain for southern European immigrants flooding into the U.S. led to the Immigration Act of 1924, which was designed to limit immigration from southeastern Europe. (This same belief in the superiority of northern over southern Europeans fueled discussion of eugenics.) [19] As President Calvin Coolidge said in his first address to Congress, "America must be kept American" [20]. This moment in the 1920s coincided with a rebirth of the KKK, whose membership spiked up to five million—the organization was so emboldened that the Klan organized marches through the streets of major cities like New York [21]. Later in the century, the focus of nativist sentiment shifted toward Latin America. The Bracero Program, which allowed migrant workers to enter the United States legally from Mexico, ended in the 1960s. Legal immigration plummeted, but the number of Mexican immigrants remained about the same; however, "two out of every five were now 'undocumented' and deemed to be illegal aliens, subject to deportation" [22]. Conversations erupted over how to prevent these undocumented immigrants from entering the country, and much of this rhetoric equated Mexican immigrants with the crime and drug epidemic, as is discussed in the "Machine Learning" tab. Many presidents under analysis in this project focus on these same immigrants in their discussions of immigration. Today, the debate over Central American immigrants still contains threads of nativism, as evident in our analysis of President Donald Trump's remarks on the matter. In recent years, a nativist animosity towards Muslim immigrants has led to attempts by the U.S. to ban travel from Muslim-majority countries.

New shoots of nativism and nativist rhetoric have episodically emerged throughout American history, newly-conceived expressions of a centuries-old fear of the foreign.

[1] Ira M. Leonard and Robert D. Parmet, American Nativism, 1830-1860 (Huntington, NY: R.E. Krieger Pub., 1979), 6.

[2] Eric Kaufmann, "American Exceptionalism Reconsidered: Anglo-Saxon Ethnogenesis in the 'Universal' Nation, 1776–1850," Journal of American Studies 33, no. 3 (1999): 441, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875899006180.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ruth Miller Elson, Guardians of Tradition: American Schoolbooks of the Nineteenth Century (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press), quoted in Eric Kaufmann, "American Exceptionalism Reconsidered: Anglo-Saxon Ethnogenesis in the 'Universal' Nation, 1776–1850,'" Journal of American Studies 33, no. 3 (1999): 446, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875899006180.

[5] Kaufmann, "American Exceptionalism," 446.

[6] Leonard and Parmet, American Nativism, 91.

[7] Jill Lepore, These Truths: A History of the United States (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018), 263.

[8] Kaufmann, "American Exceptionalism," 447.

[9] Quoted in Kaufmann, "American Exceptionalism," 453.

[10] Lepore, These Truths, 318.

[11] "Organization and Principles of the Ku Klux Klan, 1868," University at Albany, https://www.albany.edu/faculty/gz580/his101/kkk.html.

[12] Lepore, These Truths, 319, 323-324.

[13] Brian N. Fry, Nativism and Immigration: Regulating the American Dream (New York, NY: LFB Scholarly Pub., 2007), 43.

[14] Lepore, These Truths, 318.

[15] Ibid.

[16] "Governor's Special Address," Daily Alta California, April 25, 1852."

[17] Horace Davis, "Speech of Hon. Horace Davis of California, in the House of Representatives" (address, June 8, 1878).

[18] Lepore, These Truths, 336.

[19] Fry, Nativism and Immigration, 51.

[20] University of Virginia, "Harding, Coolidge, and Immigration," Miller Center, last modified July 6, 2016, accessed December 10, 2020, https://millercenter.org/issues-policy/us-domestic-policy/harding-coolidge-and-immigration.

[21] Lepore, These Truths, 410.

[22] Lepore, These Truths, 674-675.